Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands recalls everyone being ‘exceptionally polite’ but taking no notice. Had the Dutch Resistance entered the battle in Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem, the outcome of Market Garden might have been very different. Countless cities across Occupied Europe – from Athens to Belgrade to Milan to Paris – would be liberated by their own Resistance emerging from the underground. It was a fund of first-class intelligence – much of which was ignored – and it had the capacity to lead a popular uprising if only it had been called on to do so and supplied with arms. The Dutch Resistance was well organised and deeply embedded in local society. But allies on the ground who could have made the difference were sidelined. As a colossal combined-arms military operation, the staff work was superlative. And the Germans were masters at battlefield improvisation, a feature of their military doctrine since the time of the great Moltke and the wars of 18.īut even the planning was defective. It was this that prompted Lieutenant-General Frederick Browning, Deputy Commander of the 1st Allied Airborne Army, to say to Montgomery at a military conference on 10 September 1944, ‘Sir, I think we might be going a bridge too far.’įrom the inception, everything hinged on nothing going wrong but in war, things always go wrong, for the enemy – his strength, deployment, intentions, actions, willpower – is a perennial unknown.

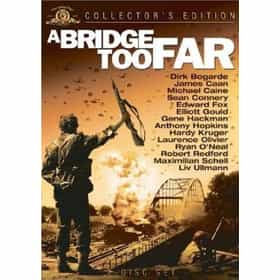

The spearhead was expected to reach Arnhem in two days. Backed-up behind the Sherman tanks of the Irish Guards in the van were some 20,000 vehicles. Much of the road was elevated on a high embankment surrounded by soft ground dissected by dykes where tanks could not operate. The British armour was required to advance some 64 miles down a single road on a two-vehicle front. Even without the Panzer divisions, the risks were high. Pictured here in the mid-1960s, he died of cancer in 1974, just months after the publication of A Bridge Too Far, his last and finest book.Ī pervasive sense of doom then hangs over everything that follows. In his job as a war correspondent, Cornelius Ryan travelled extensively, including to the Pacific and Palestine, before eventually settling in the United States in the early 1950s, where he became a naturalised citizen.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)